Background and aim:

Efficacy is a crucial concept in vaccine trials, but it’s also a tricky one. Efficacy is the degree to which a vaccine prevents disease & its transmission under a best-case scenario. Effectiveness means how vaccines perform in the worst-case scenario. A vaccine with high efficacy does not necessarily translate into the same effectiveness in the real-world setting. If a vaccine has an efficacy of, say, 95 percent, that doesn’t mean that 5 percent of people who receive that vaccine will get COVID-19. And just because one vaccine ends up with a higher efficacy estimate than another in trials doesn’t necessarily mean it is superior.

“One shouldn’t hesitate, and take an approved vaccine. The more people in a select population that is vaccinated, the lower the chances for the virus to thrive and survive and that’s why at least I have been advising folks not to choose one vaccine over another because of ‘efficacy’ numbers. But take one instead, on safety, and thorough peer-reviewed published data.”

– Syd Daftary

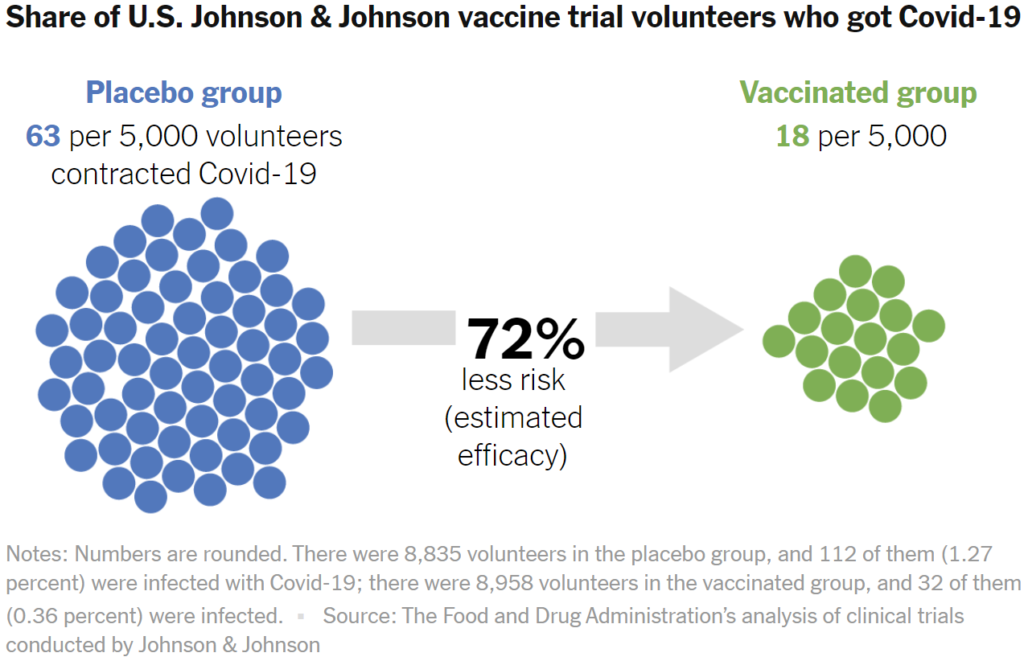

For statisticians, efficacy is a measurement of how much a vaccine lowers the risk of an outcome. For example, Johnson & Johnson observed how many people who received a vaccine nevertheless got COVID-19. Then they compared that to how many people contracted COVID-19 after receiving a placebo.

The difference in risk can be calculated as a percentage. Zero percent means that vaccinated people are at as much risk as people who got the placebo. A hundred percent means that the risk was entirely eliminated by the vaccine. In the United States trial site, Johnson & Johnson determined that the efficacy is 72 percent.

When scientists say that a vaccine has an efficacy of, say, 72 percent, that’s what’s known as a point estimate. It’s not a precise prediction for the general public, because trials can only look at a limited number of people.

The uncertainty around a point estimate can be small or large. Scientists represent this uncertainty by calculating a range of possibilities, which they call a confidence interval. One way of thinking of a confidence interval is that we can be 95 percent confident that the efficacy falls somewhere inside it. If scientists come up with confidence intervals for 100 different samples using this method, the efficacy would fall inside the confidence intervals in 95 of them.

Confidence intervals are tight for trials in which a lot of people get sick and there’s a sharp difference between the outcomes in the vaccinated and placebo groups. If few people get sick and the differences are minor, then the confidence intervals can explode.

Read More>> The New York Times | Vox